This part of the academic year marks something of a ‘changing of the guard’, as some colleagues finish a year of research leave, and others begin their own period of research leave. One person from the Centre of Law and History Research who was ‘away’ in 2020-21 was our resident Scots law and legal history specialist, Dr Chathuni Jayathilaka. A quick interview for the blog seemed in order, to see what she has been up to, and to document the experience of pandemic research, for the legal historians of the future. She was duly cornered and interrogated by Gwen Seabourne.

GS: How has it been, trying to do research in this oddest of years, Chathuni? What difficulties have there been, and have you found any creative ways around them?

CJ: It’s been an interesting experience! I have been surprised by how much you can do with just a laptop, a good internet connection, the university library’s subscription to various databases and the aid of resourceful librarians. But there have been limitations as well: I had to redesign my projects for this year because I realised that the projects as originally conceived would run into problems created by an inability to access key sources. I’m not sure redesigning an entire project counts as finding a creative way around the problem…

GS: What have you been researching?

CJ: I have been working on two papers, both to do with the law’s response to supervening events which render contractual performance impossible. The first paper explores why the English contract of sale for goods has both a doctrine of frustration and a rule on the passing of risk. The second paper examines the concept of fault in relation to supervening events through a historical lens.

GS: Why? What is interesting about this area and how does it relate to what you have done before?

CJ: My previous research has been on the contract of sale [officious interjection by GS – See Chathuni’s book on this topic and her responses to another interrogation about it, a little while ago], so there is a link in that I am still looking at the same contract. But really, this project has even earlier roots. My undergraduate dissertation examined the law’s response to supervening events which render contractual performance impossible. I am not sure what it is about the topic that fascinates me – I think it may be the exploration of the idea that in certain situations, the law will allow you to escape liability. Why, when and to what extent is truly intriguing.

GS: ‘Supervening events’ does seem to be a very topical matter, as we have all been working through a rather large and, to most of us, unexpected event in this pandemic year. As you say, it has meant some changes of plans, and some impetus to read into new areas. What have you read this year that has got you thinking, or inspired you?

CJ: My previous work has been on Scots private law. The two papers I have been working on over the past year were initially meant to focus on Scots law, but the pandemic then intervened. Without any reliable way of accessing the Scots law sources I needed, I had to rethink both papers and shift the focus onto English law. I have spent a lot of the last year reading around English legal history, and particularly the development of English contract law. This pushed me out of my comfort zone and meant that my work progressed at a slower pace than I would have liked it to but having the time and mental space to get to grips with this subject has been a real luxury. It’s the sort of thing I would not have been able to do in the snatched research days we get during an ordinary teaching year.

GS: Apart from legal history, what has got you through the year?

CJ: I have had a lot more time to read for pleasure over the last year and have really enjoyed this. Last summer, I also took a short course in short story writing, which is something I have wanted to do for a long time. It’s been fun writing and reading for pleasure rather than purely for work.

GS: How has it been coming to historical common law sources and the history of common law after specialising in Scots law and its history? What strikes you as odd, or difficult, or especially interesting?

CJ: To begin with, it was like learning to read a different language. I am well versed in modern English contract law as I teach it to undergraduates and there is a degree of overlap between it and modern Scots contract law. But the historical law is another story.

Scots contract law is quite systematised. In contrast, I found historical English contract law to be contradictory and chaotic. I had to get my head around both unfamiliar terminology and the different structures and methods of this new (to me!) system. Then there was the thorny problem of understanding the citation system for older cases and learning how to track particular cases down. Luckily, one of my colleagues at the Centre was able to explain this to me. But for all the difficulties, there are also advantages. The chaos of the English system appeals to me in a way because there is more of a puzzle to unpick. English sources – both primary and secondary – are also a lot more accessible and are greater in volume. With Scots law, you often find that very little has been written about particular topics – this is not so much the case with English legal history.

GS: When we look at older private law sources, we often end up having to get to grips with unfamiliar trades and businesses (e.g., just recently I have been immersing myself in the cattle markets and butchery trade of 19th C Halifax, for one of my legal history projects). I know you have previously read a LOT about horse sales (for Dr Jayathilaka and a horse, see picture, above). What other specialised areas have you been exposed to in your work?

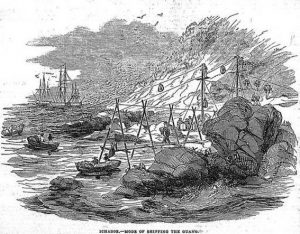

CJ: Well, I’ve discovered that there was at one point a feverish trade in guano. Guano – the droppings of seabirds and bats – was used as fertiliser and a particularly good form of it was found on the island of Ichaboe (located off the coast of Namibia). Guano was such a sought-after commodity that there were even guano pirates! I actually first came across the guano trade during my PhD, when there was a case featuring a dispute over the quality of the guano delivered, Paterson v Dickson (1843) 5 D 402. My external examiner was so tickled by this case that at the end of the viva he gave me a printed out copy of a guano poem (a little-known literary sub-genre…).

Where penguins have lived since the flood or before,

And raised up a hill there, a mile high or more.

This hill is all guano, and lately ’tis shown,

That finer potatoes and turnips are grown,

By means of this compost, than ever were known;

And the peach and the nectarine, the apple, the pear,

Attain such a size that the gardeners stare,

And cry, “Well! I never saw fruit like that ‘ere!”

One cabbage thus reared, as a paper maintains,

Weighed twenty-one stone, thirteen pounds and six grains,

So no wonder Guano celebrity gains.

GS: Thank you for that, Chathuni. Can’t say I was expecting to learn about guano-focused literature today! (pauses to take it all in and refocus). What are you looking forward to, when you return to teaching?

CJ: Research leave is a real luxury, but I have also missed the cycle of the academic year. It will be nice to see more of my colleagues, to get back into teaching and to simply be on campus again. I am particularly looking forward to coming back and teaching Roman law. The study of Roman law is an important intellectual tradition and some decades ago, most English law schools would have offered a course on it. This is sadly no longer the case, but we are proud to still be able to offer it to our students at Bristol.

GS: And finally, what do you want future legal historians to know about 2020-21, and the experience of researching during a pandemic?

CJ: We would all be lost without librarians and their dogged ability to source obscure texts even when libraries have been shut, physical books cannot be borrowed or browsed, and budgets have been slashed.

GS: Quite so.

Thank you Chathuni, and we look forward to seeing your work on supervening events, and perhaps the odd horse- or guano-related short story, in due course!

And so we leave Dr Jayathilaka to ride off into the distance (see picture, above) and prepare herself for the joys of a new academic year.