The invention of the printing press revolutionised law reporting. Medieval lawyers had relied less on written texts than on their profession’s ‘common learning’, which was passed down orally at the Inns of Court. Students learnt by observing the courts at work, but also by listening to senior lawyers discussing the law at moots or even over dinner. They rarely cited specific case reports in court, instead referring vaguely to ‘our books’. More precise references would have been unhelpful – after all, manuscript law reports were difficult to access and not necessarily consistent. The appearance of reliable and widely-distributed printed reports encouraged lawyers to cite cases much more extensively.

In the sixteenth century, though, the printed reports available were often decades out of date. Lawyers therefore relied on circulating manuscript case reports to keep on top of new material, and to glean information that the printed reports didn’t provide. We can get an insight into how these cases were shared between lawyers by looking at a manuscript report of the 1567 ‘serjeants’ case’. Serjeants were an elite rank of barristers with special privileges. When a new batch of serjeants was appointed, there would be celebratory feasts and amusements, including a serjeants’ case: a hypothetical case invented for the new serjeants to debate. (Imagine newly-appointed QCs taking part in a moot for their colleagues’ entertainment.)

Like many moot problems today, the serjeants’ case of 1567 was based on a real contemporary case. It concerned the intricacies of will-making. For example, if a testator made a will of ‘all his land’, but acquired new land after making the will, would the new land pass by the previous will? Questions like this were very controversial. Wills of land were new to the common law – they had only been permitted by the 1540 Statute of Wills – so lawyers were still unsure exactly how they should work. The serjeants’ case would have been watched with interest to see what these top barristers thought about the problem – perhaps it would give some clues about what would happen when the real case was argued the following year.

One reporter, Edmund Plowden, even included some arguments from the serjeants’ case in his printed report of the real case, Brett v Rigden (1568) Plow 340. Brett was argued by Roger Manwood and William Lovelace, two of the newly-appointed serjeants. Plowden, always conscientious, explained that he had missed part of the argument in Brett, and would therefore ‘repeat some things which were said’ by Sjts Manwood and Lovelace in the serjeants’ case the year before. Plowden’s report was published in 1571 – very speedy by the standards of the sixteenth-century press.

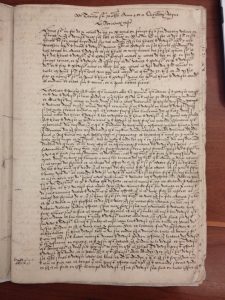

However, it was a disappointment to some lawyers. They wanted to hear more about the serjeants’ case – it had been argued by seven new serjeants, but Plowden had only reported the arguments of two. To fill this gap, they turned to another report of the serjeants’ case, which had not been printed, but which was available in manuscript. The Huntington Library holds a copy of this report as part of its Ellesmere collection, meaning that it was once owned by Thomas Egerton, Baron Ellesmere – a senior judge who prosecuted Mary, Queen of Scots, acted as James I’s Lord Chancellor, and employed John Donne as his secretary. The manuscript is professionally written and presents the arguments of all seven serjeants in great detail – it is even longer than Plowden’s report of Brett.

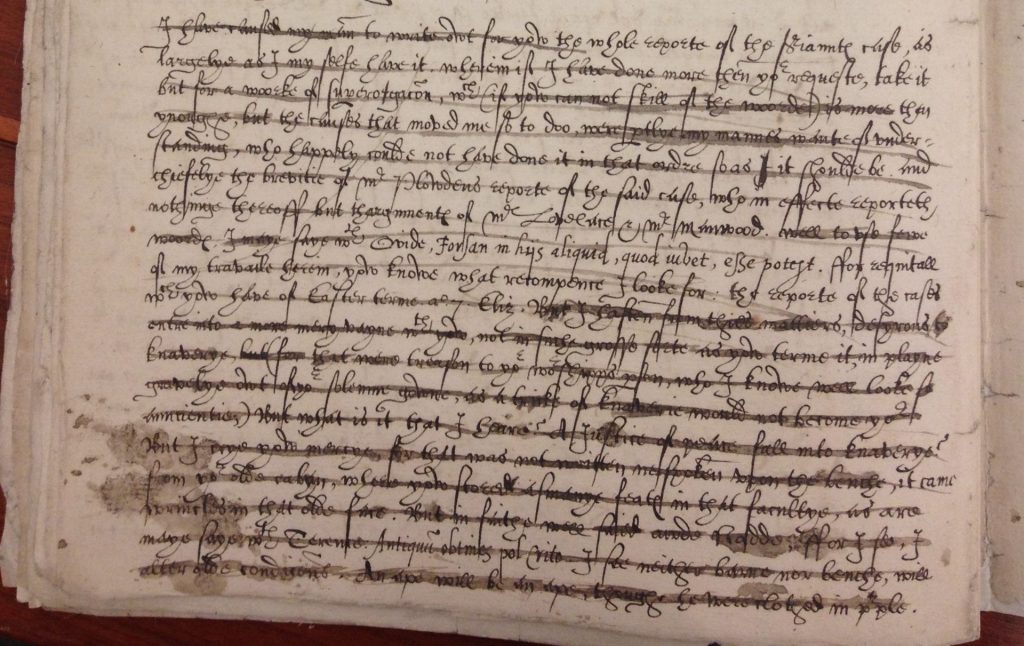

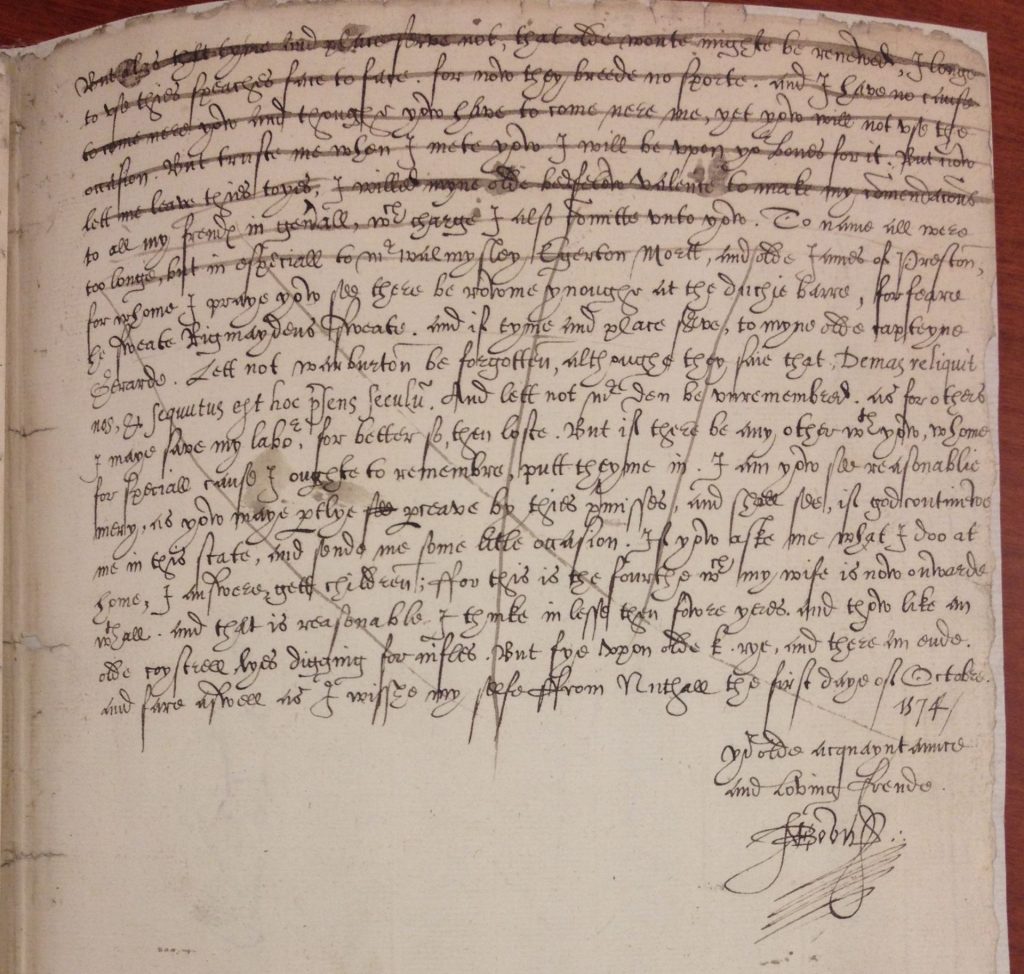

Where did this manuscript come from, and how did Egerton get hold of it? Helpfully, a letter appended to the bottom of the report gives us some insight into its history. The letter was written on 1 October 1574 and signed by a John Boune. He explains, ‘I have caused my manne to write owt for yow the whole reporte of the seriaunts case, as largely as I my selfe have it’. He had two reasons for making sure that the report was a full one: not only did his clerk lack the legal knowledge to condense it, but he was ‘chiefelye’ concerned about ‘the brevitie of Mr Plowdens reporte of the said case, which in effecte reporteth nothinge thereoff but tharguments of Mr Lovelace & Mr Manwood’. He wasn’t providing the report for free, though: ‘For requitall of my travaile herein, yow knowe what recompence I looke for: the reporte of the cases which yow have of Easter terme anno 7 Eliz’ (1565).

Boune and his correspondent were clearly trading manuscripts of the law reports to which they each had access. Interestingly, Boune wanted some real case reports, but he was only sending a report of arguments in a moot. That might seem odd to today’s lawyers, who are usually interested in reading the authoritative judgments of courts. However, in Boune’s period, the doctrine of precedent was still in its infancy. In the Middle Ages, lawyers wanted to learn arguments that accorded with the common learning, wherever they happened to have been made. It was only in the Tudor period that the arguments made in judicial decisions became the key authorities. Plowden’s reports, which focused on judgments, were a good example of this new style of law reporting. The circulation of this manuscript report shows that there was still demand for legal sources that were not court decisions.

The lawyer who corresponded with Boune isn’t named in the letter. However, we can be sure that it wasn’t Egerton. In his letter, Boune sends ‘commendacions to all my frends in generall… but in especiall to me Walmysloy Egerton Mortt’. So Egerton wasn’t the original recipient of the manuscript, which continued to circulate. Egerton, though, must have known both Boune and his correspondent. Boune also refers to his friend as a justice of the peace, but that isn’t much help in identifying him – there were several dozen JPs in each English county, so the list of candidates is still a long one.

Are there any other clues in the letter? Boune joined Lincoln’s Inn in 1560, at around the same time as Egerton and some other lawyers mentioned in the letter (including Thomas Walmesley and Thomas Morte). Perhaps Boune’s correspondent was another friend from his student days? He certainly makes reference to what sounds like student mischief when he teases his correspondent about some recent gossip: ‘But what is it that I heare? A Justice of peace fall into knaverye? … I maye saye with Terence: Antiquu obtines pol Crito [truly, Crito, you adhere to your old ways]. I see neither barre nor benche, will alter olde condicions.’ On the other hand, he also jokes about the ‘wrincles’ in his friend’s ‘olde face’. Given that most students joined the Inns of Court at around the age of 20, Boune’s student friends were likely not that old – Egerton, for example, was 34 in 1574.

I haven’t yet identified the recipient of Boune’s letter (and I’d love to hear any suggestions!) It’s clear, however, that the two men were close. Boune wrote that he longed to see his correspondent and berated him for not visiting. He also shared some personal news: his wife was pregnant with their fourth child, ‘and that is reasonable I thinke in lesse then fowre yeares’. Someone, possibly Egerton, has rather impatiently crossed out these pleasantries, no doubt irritated that they were intruding on his law report. For us, though, they provide a fascinating insight into the legal culture of the time. They show the demand for manuscripts that could fill gaps in the printed law reports, and the way that demand was supplied by lawyers – not just as a professional courtesy, but also as a sign of friendship.

(Speaking of helpful friends: my thanks go to David Foster for his help with transcribing Boune’s letter!)

well post

Nicely written. 192.168.1.1