(This post appeared on the University of Bristol Law School Blog in February 2024)

The common law of England, in the medieval centuries and long afterwards, was man-made law: created by and in the interests of free men, drawing on and reinforcing ideas of women as inferior. Its assumption of the superiority of men was intensified during marriage, with the wife’s identity defined in relation to her husband, her legal personality subordinated to his in important respects. Studying the documentation left behind by those making, administering and using the common law in medieval England provides ample confirmation of the disadvantages and limitations which were imposed upon women and the hierarchical nature of marriage. Amongst the many records which seem to show settled, hierarchical ideas, there are, however, occasional glimpses of subtler thinking and richer detail, serving both to nuance our view of medieval thinking about law and gender, and also to expand our understanding of the lives of medieval women, up to a point. Such glimpses can be found in the documentation relating to an episode in the later fifteenth century, and subsequent legal action, which I will note here.[i]

A northern English landowner, Sir John Assheton, alleged that, on a November night in 1470, a group of more than 200 ‘riottours’, headed by a certain John Myrfeld and Richard Ledys, attacked his manor of Howley (Morley, Yorkshire). They were, he said, brandishing a fearsome array of weapons, and they came with trumpets and horns blaring, damaging his property pulling walls down and deliberately setting fires, and causing considerable fear to his household, including his wife, her female companions and his servants. He himself had been taken away to nearby Pontefract Castle, and made to seal a bond for £1000 in their favour, obliging him to do what they wanted. He petitioned for the aid of king (Edward IV) and parliament, to ensure that he was able to take effective legal action against multiple miscreants.

So far, so stereotypically masculine: men and property; men and violence; men and their weapons; an exclusively male parliament and legal profession; a male monarch, a wife whose name is not thought worth noting. There are, however, valuable references to women, and hints about gender ideas, in the petition in which Assheton told this story, and in the wider body of documentation on the case.

In the petition, Assheton suggested that the attack was particularly serious because of its effect on his wife and the women attending her. His anonymous spouse had, he said, just had a baby, and was still ‘in child-bed’. She was very frightened by the attack, then and for a long time afterwards. Assheton did eventually say that he experienced ‘fere’ but only after he had attributed even stronger emotions to his ‘wif’, describing her as being ‘in right grete dispare of hir lif’, and noting that the ‘gentilwomen’ who were with his wife, shared her feelings.

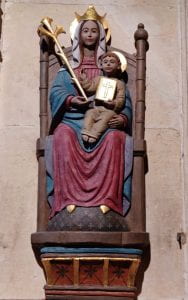

In addition to the emotional impact on his wife, he also stressed the danger which would have been involved in moving her away from the scene of the attack: at that point just after her delivery: moving her would be a risk to her life (putting her in ‘ieop[ar]dy of hir deth’). The possibility of death in or after childbirth was much on the minds of medieval people, and the petition also alludes to one of the ways in which they might choose to improve the chances of a good outcome. Describing the situation of his wife, Assheton’s petition mentions that she was, at the time of the attack, lying ‘in the bandes (or, in one instance, ‘bondes’) of ‘Our Lady’. This important, and rather intimate, detail, referring to the Virgin Mary and the possibility of her assistance in childbirth, might conceivably be metaphorical, but I think that it is rather more concrete than that, and indicates the use of a particular supernaturally-charged device: the birth girdle. Such belts, or girdles, inscribed with prayers for the safety of the wearer, and sometimes invoking the aid of Mary, have aroused the interest of historians of medicine, religion and gender for some time, and a recent scientific study of one surviving girdle gave strong evidence of the fact that it was actually wrapped around the body of the woman during childbirth.[ii] This documentary evidence may extend understanding of the use of such objects a little, suggesting as it does that a woman might remain girdled for a time after the delivery, and also that the use of the girdle was sufficiently well-known to laymen to make it a useful ‘plot element’ in a non-specialist medical or religious narrative.

The other detail of the petition’s birth story which is worth emphasising is the surrounding of the labouring and newly-delivered wife by other women, confirming the idea of confinement as a period in which one would expect female-only company (unless there was some emergency).[iii] While male medical professionals were increasingly claiming gynaecology as part of their intellectual domain,[iv] this account reinforces the idea of childbirth usually being a women-only event.