New law students often experience academic culture shock. As Russell Sandberg writes, ‘Law Schools are strange places’, where students are expected to solve unusual problems, use a unique set of sources, and employ distinctive methods. They are asked to ‘think like lawyers’, even when these new ways of thinking are ‘at odds with what law students have previously experienced’. Happily, help is close at hand: there is no shortage of books written by distinguished lawyers who are anxious to explain to new law students what the law is and how they should approach its study.

Law students’ culture shock is not a uniquely modern phenomenon, and nor is experienced lawyers’ instinct to offer well-meaning advice. Early modern law students had plenty of complaints as they began their studies at the Inns of Court. They were not offered official reading lists or introductory courses: instead, they were expected to read their way through the case law by themselves. Many students were shocked by the heavy workload and lack of clear direction. Henry Spelman described his work as ’a mass which was not only large, but which was to be continually borne on the shoulders’, while Abraham Fraunce complained that ‘the study of the Law’ was ‘hard, harsh, unpleasant, unsavory, rude and barbarous’.

Lawyers soon began to publish books of advice to help these struggling law students. Some instructed students on how they should spend their time. In 1663, for example, Edward Waterhouse recommended the following (rather varied) timetable to law students: 5-6am was for reading the Bible and praying; 6-9am was for reading law; 9-11am for fencing and dancing; 11am-12 noon for learning logic and rhetoric; 12-2pm for eating; 2-5pm for visiting friends; 5-6pm for reading poetry; 6-8pm for eating again; and 8-9pm for praying before bed.

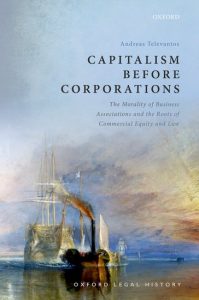

We in the Centre for Law and History Research enjoy nothing more than curling up with a good book! For our first post this year, we caught up with another legal historian, Andreas Televantos (University of Oxford), whose book Capitalism before Corporations: The Morality of Business Associations and the Roots of Commercial Equity and Law (OUP 2020) recently won the SLS’s Peter Birks Prize for Outstanding Legal Scholarship. Our roving reporter went to find out more…

We in the Centre for Law and History Research enjoy nothing more than curling up with a good book! For our first post this year, we caught up with another legal historian, Andreas Televantos (University of Oxford), whose book Capitalism before Corporations: The Morality of Business Associations and the Roots of Commercial Equity and Law (OUP 2020) recently won the SLS’s Peter Birks Prize for Outstanding Legal Scholarship. Our roving reporter went to find out more…