I’m currently writing about a work called Epieikeia: A Dialogue on Equity in Three Parts, which was composed by Edward Hake in the late sixteenth century. Hake was a Puritan, a poet, and a local government official, who hoped that his treatise would bring him to the King’s attention and secure his advancement. If I’m honest, I first became interested in this work because it’s more than a little bizarre.

For a start, it’s written in dialogue form—as an imaginary conversation between Hake and two friends, Lovelace and Eliott. The conceit is that the three men have gathered before dinner when Eliott starts pressing Hake to explain to them the nature of equity (as you do). Hake is initially reluctant, but is soon convinced to spend three afternoons (or 140 pages) expounding his ideas.

The literary dialogue was popular in Renaissance Europe, and many writers used it to draw out a range of views and ambiguities around their topic. Hake… did not. Lovelace and Eliott are really only there to repeat his conclusions and tell him how clever he is. (Sample contribution from Eliott: ‘I acknowledge to have received both pleasure and profitt [from Hake’s discussion], pleasure in the variety of the matter, and profitt in the good end and purpose that hath byn of it. And this I must confesse, that had it not byn for this and your former speache, I sholde have remained in error…’) It’s a shame that this mode of writing has fallen out of fashion—it must be good for the self-esteem and a helpful cure for writer’s block.

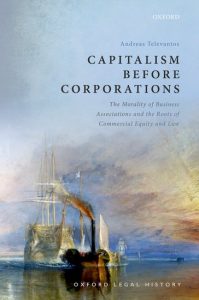

We in the Centre for Law and History Research enjoy nothing more than curling up with a good book! For our first post this year, we caught up with another legal historian, Andreas Televantos (University of Oxford), whose book Capitalism before Corporations: The Morality of Business Associations and the Roots of Commercial Equity and Law (OUP 2020) recently won the SLS’s Peter Birks Prize for Outstanding Legal Scholarship. Our roving reporter went to find out more…

We in the Centre for Law and History Research enjoy nothing more than curling up with a good book! For our first post this year, we caught up with another legal historian, Andreas Televantos (University of Oxford), whose book Capitalism before Corporations: The Morality of Business Associations and the Roots of Commercial Equity and Law (OUP 2020) recently won the SLS’s Peter Birks Prize for Outstanding Legal Scholarship. Our roving reporter went to find out more…